Does a fault break all at once?

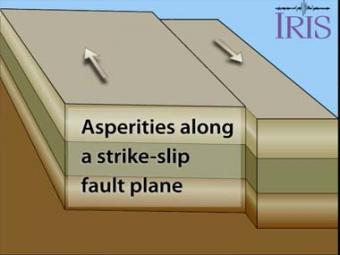

Oblique view of a right-lateral strike-slip fault with multiple asperities. When one asperity slips, there is an added load on the adjoining asperities. In a large earthquake there is a cascading effect as each zone that slips loads the next zone, which then slips, and so forth, sometime for hundreds of miles, in a process that can continue for 5 or more minutes. An asperity is an area on a fault that is stuck or locked. Scientists study areas along long fault zones that have not had earthquakes in a long time in order to determine where the next earthquake may occur; as long faults move, all areas of it will, at some point, become "unstuck" causing an earthquake relative to the the size of the asperity that finally breaks.

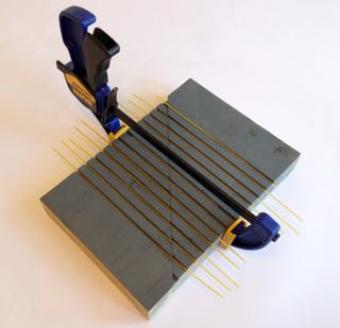

This demonstration, squeezing uncooked spaghetti noodles in a wood template set in a vise, effectively shows how asperities (stuck patches) on a fault rupture at different times.

How can I demonstrate plate tectonic principles in the classroom?

Video lecture demonstrates the use of foam faults to demonstrate faults, and a deck of cards to demonstrate folds and fabrics in rock layers. Different types of faults include: normal (extensional) faults; reverse or thrust (compressional) faults; and strike-slip (shearing) faults.

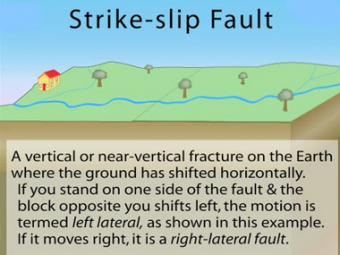

In a strike-slip fault, the movement of blocks along a fault is horizontal. The fault motion of a strike-slip fault is caused by shearing forces. Other names: transcurrent fault, lateral fault, tear fault or wrench fault. Examples: San Andreas Fault, California; Anatolian Fault, Turkey.

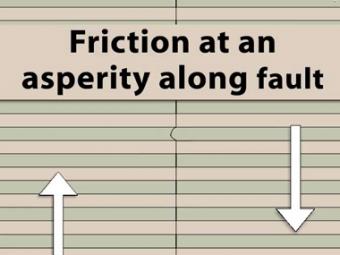

View looking into a fault zone with a single asperity. Regional right lateral strain puts stress on the fault zone. A single asperity resists movement of the green line which deforms before finally rupturing.

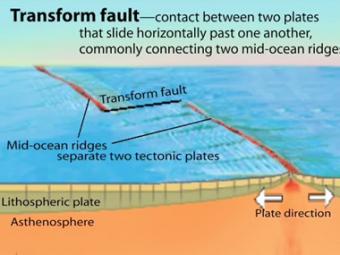

A transform fault is a type of strike-slip fault wherein the relative horizontal slip is accommodating the movement between two ocean ridges or other tectonic boundaries. They are connected on both ends to other faults.

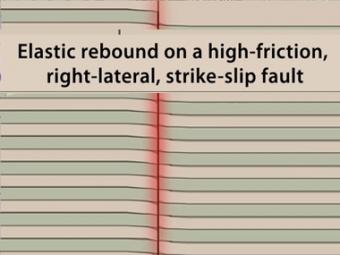

Animation shows the buildup of stress along the margin of two stuck plates that are trying to slide past one another. Stress and strain increase along the contact until the friction is overcome and rock breaks.

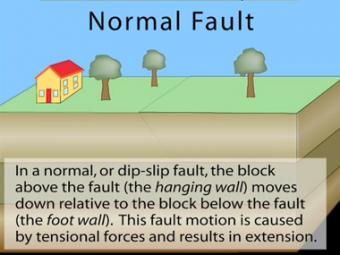

In a normal fault, the block above the fault moves down relative to the block below the fault. This fault motion is caused by extensional forces and results in extension. Other names: normal-slip fault, tensional fault or gravity fault. Examples: Sierra Nevada/Owens Valley; Basin & Range faults.

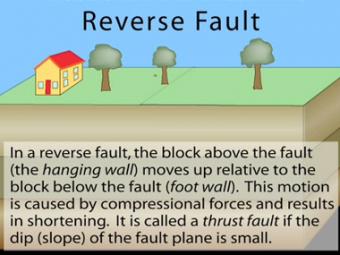

In a reverse fault, the block above the fault moves up relative to the block below the fault. This fault motion is caused by compressional forces and results in shortening. A reverse fault is called a thrust fault if the dip of the fault plane is small. Other names: thrust fault, reverse-slip fault or compressional fault]. Examples: Rocky Mountains, Himalayas.

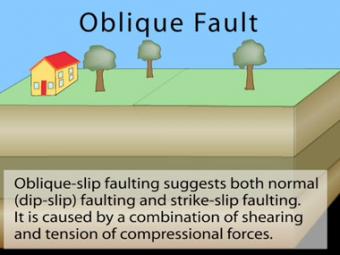

This left-lateral oblique-slip fault suggests both normal faulting and strike-slip faulting. It is caused by a combination of shearing and tensional forces. Nearly all faults will have some component of both dip-slip (normal or reverse) and strike-slip, so defining a fault as oblique requires both dip and strike components to be measurable and significant.

Squeezing uncooked spaghetti noodles in a wood template set in a bar clamp, effectively models how asperities (stuck patches) on a fault rupture at different times.

We encourage the reuse and dissemination of the material on this site as long as attribution is retained. To this end the material on this site, unless otherwise noted, is offered under Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license